By Dr Shoona Vincent, Vice President of Clinical Science at MAC Clinical Research

The psychedelic research renaissance is well underway, with clinical trials investigating psilocybin, MDMA and other compounds yielding promising results for conditions such as treatment-resistant depression, PTSD and anxiety. Yet as a clinical scientist working at the intersection of research and care, I’m increasingly aware that the biggest challenge may lie not in the trials themselves, but in what happens next.

How do we responsibly, ethically and effectively translate psychedelic research into real-world healthcare settings?

While data from early-phase trials has sparked optimism, moving from controlled environments into the complexity of public health systems like the NHS is far from straightforward. Without careful attention to this translational gap, we risk undermining both patient safety and scientific credibility.

Clinical trials, by design, operate under highly controlled conditions. Participant selection is highly controlled and carefully managed. Interventions are delivered according to strict protocols. Staff are extensively trained, and safety oversight is constant. These are necessary conditions for generating reliable data, particularly when dealing with powerful psychoactive compounds.

But real-world clinical care is not a controlled environment. In the UK, for example, the NHS is already stretched for resources, and psychedelic therapies, which often require extended therapeutic sessions, careful preparation and post-treatment integration, are resource intensive. Even in private healthcare, logistical and legal barriers persist. Scaling psychedelic therapy demands a reimagining of how such care could be delivered.

The patient population in clinical trials is also often narrow by necessity. In practice, individuals seeking psychedelic treatment may present with comorbidities, complex trauma histories, or physical health conditions that were excluded from trials. These variables challenge both safety assumptions and efficacy predictions.

Psychedelic compounds are not like conventional medicines; their effects are profoundly shaped by context: the “set and setting” often referenced in psychedelic literature. Ensuring appropriate therapeutic environments, including trained facilitators and immediate access to psychiatric or medical support, is essential to minimising risk.

From my experience in psychedelic clinical research, one of the most underestimated logistical challenges is staffing. Delivering psychedelic therapy safely requires coordination between facilitators, psychiatrists, raters, medics and support staff, often outside standard working hours. Screening processes are necessarily selective to manage this risk and ensure participants have the appropriate support systems in place during and after dosing.

In trials we also confront the issue of functional unblinding, a challenge unique to psychedelics due to their unmistakable psychoactive effects. This complicates assessments of treatment efficacy and placebo effects. To counter this, we’ve found it crucial to use blinded outcome raters and maintain strict controls around data collection.

Translating all of this into a typical mental health care setting will be no easy task.

Another challenge lies between the standardisation required in research and the personalisation needed in practice. Psychedelic therapies elicit deeply individual experiences, influenced by a person’s psychological background, life history, cultural identity and expectations. Unlike pharmacotherapies with more predictable dose-response curves, psychedelics can vary dramatically in effect, even with identical doses.

This makes it difficult to produce a “one-size-fits-all” treatment model. We must acknowledge that understanding efficacy means going beyond statistical outcomes and engaging with the lived experience of participants. Some may benefit from one or two sessions; others may require longer integration support. For some, these therapies may not be appropriate at all.

This has long been a challenge in mental health care, but psychedelics magnify it. We need to find ways to balance generalisable findings from randomised controlled trials with flexible, context-sensitive approaches in practice. The aim is not to compromise on scientific quality, but to build on it by acknowledging that complexity and subjectivity are part of the therapeutic process.

To bridge the gap between clinical trials and real-world application, we need to diversify our approach to evidence generation. In my opinion traditional outcome measures, while valuable, are not enough.

We need to understand the phenomenology of psychedelic experiences, how people interpret and integrate these sessions into their lives, how meaning is constructed and how this affects therapeutic outcomes. Qualitative methods can surface insights that quantitative data often misses: fears, breakthroughs, cultural dimensions and personal transformations that shape the healing process.

Only by incorporating these insights can we develop more nuanced clinical guidance, train facilitators appropriately, and create ethical frameworks for expanded access.

What Comes Next?

We are at a pivotal moment. The enthusiasm surrounding psychedelic therapies is justified but must be tempered by realism and responsibility. Moving from trial to treatment will require more than good data; it demands thoughtful implementation, strict safety protocols, flexible care models and a willingness to embrace complexity.

At a recent CNS Summit, there was consensus among attendees that while psychedelic-assisted therapies hold great promise, psychotherapy may not be required in all general practice contexts. This reinforces the need to avoid rigid, one-size-fits-all models and instead prioritise flexible, patient-centred approaches grounded in both evidence and clinical judgement.

As researchers, clinicians, and policymakers, we must collaborate across disciplines to ensure that psychedelic care is not only effective, but also equitable, ethical, and evidence informed. The success of this field will depend not just on what we discover in the lab but on how we adapt it to meet the needs of real people, in real clinical settings.

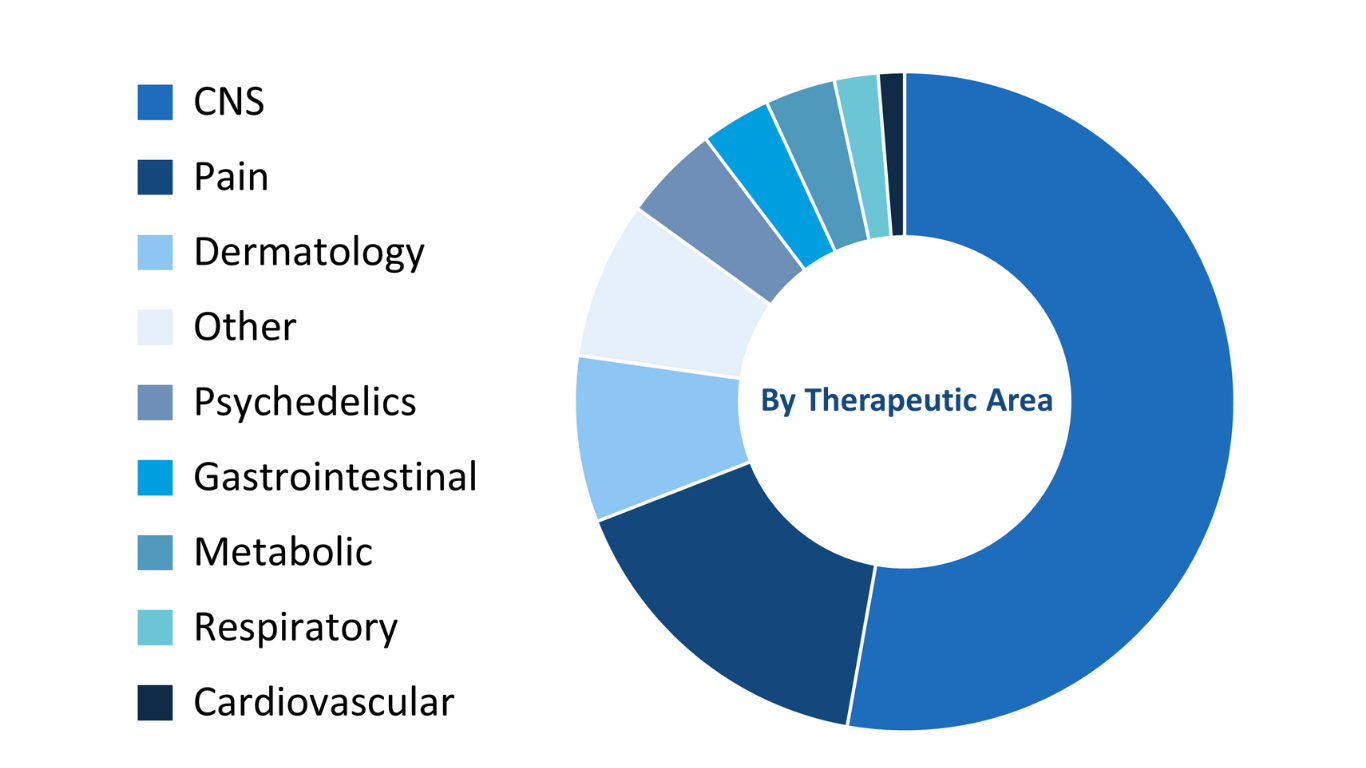

Dr Shoona Vincent has over 35 years of experience in the pharmaceutical and CRO industry, leading global clinical research programmes across multiple therapeutic areas. Since joining MAC Clinical Research in 2014, Dr Vincent has overseen several psychedelic studies and continues to advise sponsors as a Therapeutic and Scientific Advisor.